Wall Street took betting, called it finance, sued the regulators, and walked away with billions. Here's how the con works.

So here's a story about American innovation. A 29-year-old Brazilian woman who trained as a ballerina, interned at Bridgewater Associates and Citadel, and then figured out how to make sports gambling legal by calling it something else. She's now worth $1.3 billion. Good for her, right? The American dream, immigrant success story, all that inspirational stuff Forbes loves to package for its morning motivation porn.

Try Kalshi and we both get $10

Except the actual story is about how Wall Street took an activity that's illegal in most states (sports betting), wrapped it in financial services language ("event contracts"), sued federal regulators to force approval, and is now printing money while DraftKings and FanDuel watch their business model get eaten by competitors who figured out the magic words that make gambling legal when you say them with an MIT degree.

Luana Lopes Lara and her co-founder Tarek Mansour launched Kalshi in 2018. The pitch was simple: let people trade on the outcomes of future events. Elections, interest rate decisions, Oscar winners, sports games. You think the Fed's raising rates? Buy a contract. You think the Cowboys are covering the spread? Buy a contract. It's not gambling, see. It's a "prediction market." Totally different thing.

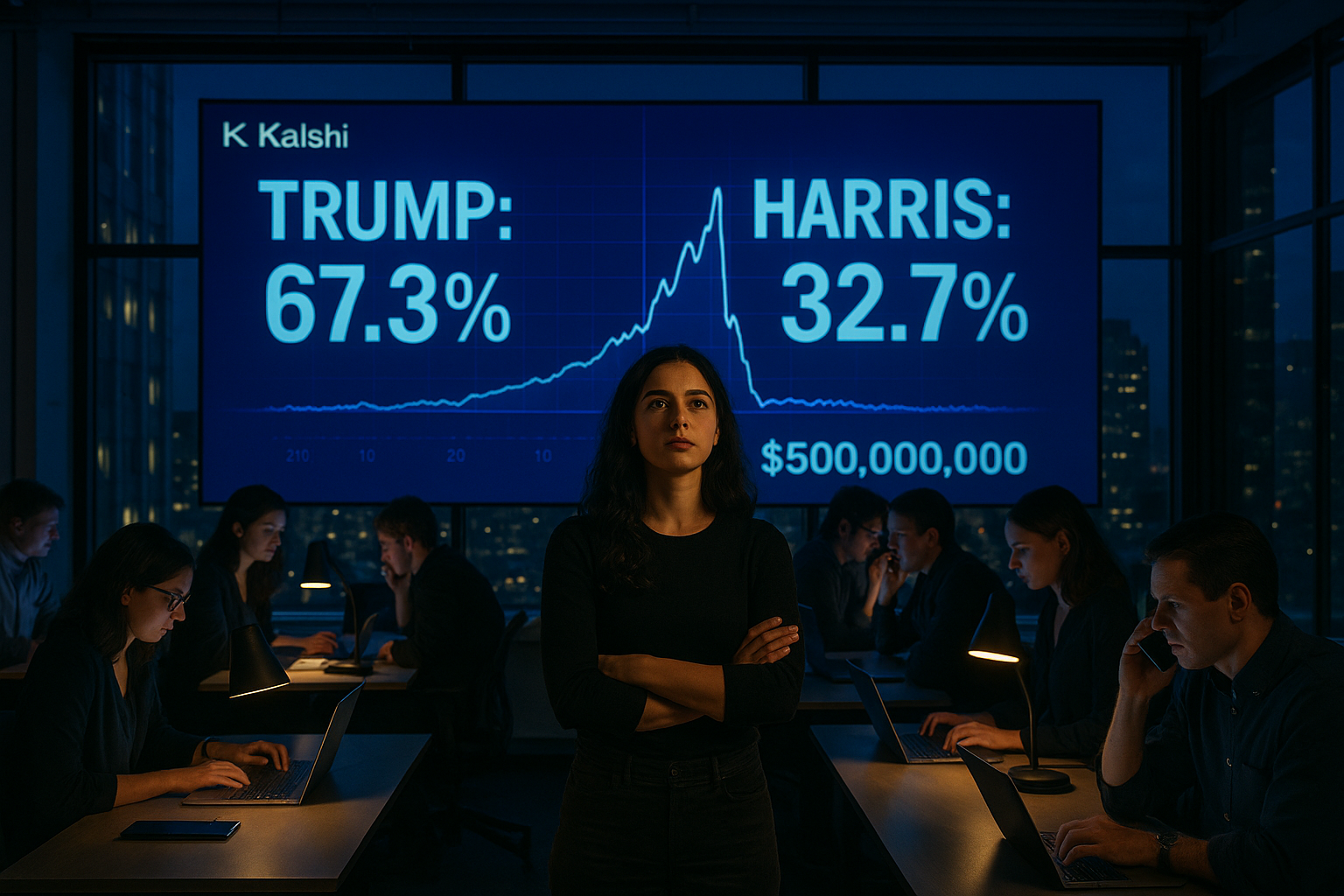

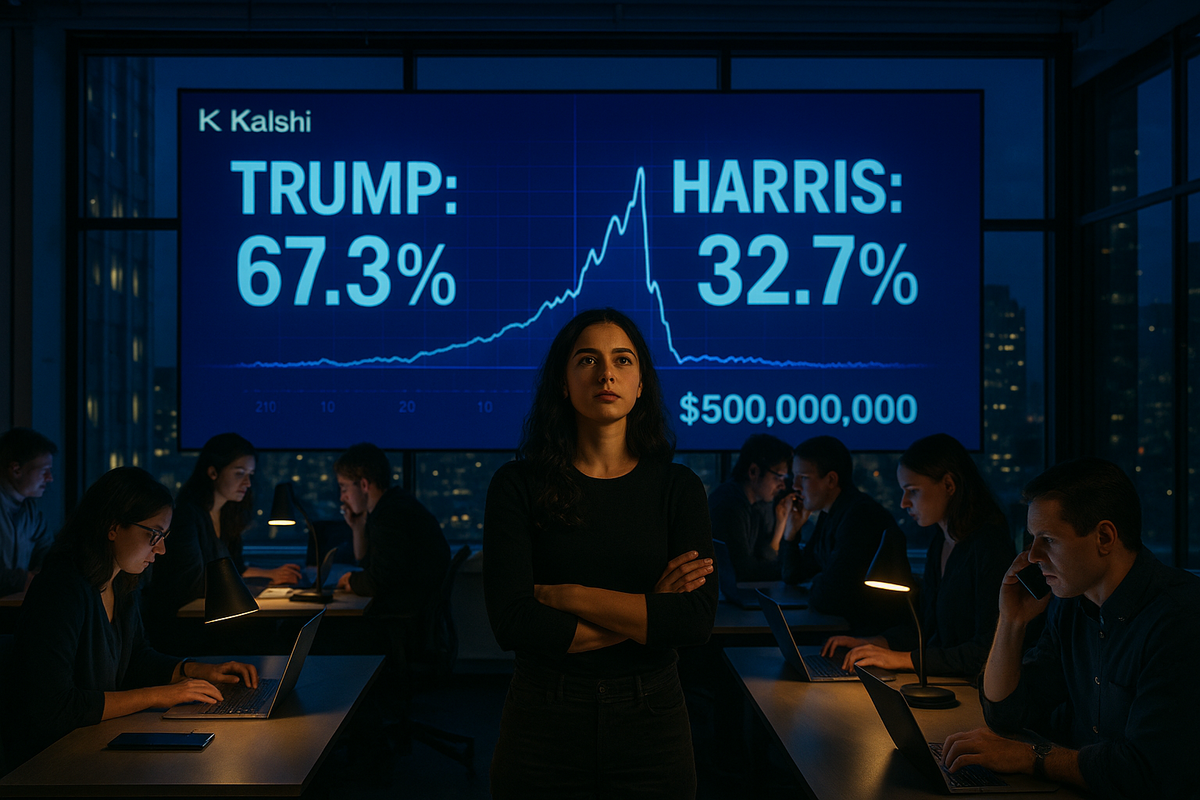

By December 2025, Kalshi raised $1 billion at an $11 billion valuation. The company went from a $2 billion valuation in June to $11 billion in December. That's not growth. That's a gold rush. And 80% of the volume on the platform? Sports betting. The thing that's illegal in most of America unless you're doing it through state-licensed casinos or the few online platforms that fought through decades of legal battles to operate.

But Kalshi isn't a casino. It's a "regulated event-contract exchange." See the difference? Neither does anyone placing bets on Monday Night Football, but the Commodity Futures Trading Commission does, and that's what matters.

How the Con Works

Here's the beautiful part. Sports gambling has been mostly illegal in the U.S. for decades. The 1992 Professional and Amateur Sports Protection Act banned it in most states. DraftKings and FanDuel spent years fighting legal battles, getting banned in states, paying fines, navigating a patchwork of regulations. They had to wait until 2018 when the Supreme Court struck down PASPA to even operate legally in most places. Even now, they're banned in multiple states and heavily regulated everywhere they operate.

Kalshi looked at this situation and asked a clever question: what if we don't call it gambling?

The CFTC regulates futures and derivatives. These are financial instruments that let you bet on (sorry, "take a position on") future events. Commodity prices, currency rates, interest rates. Sophisticated stuff for sophisticated people. Not gambling. Finance.

So Kalshi applied to the CFTC for approval to operate an exchange for "event contracts." These contracts let you bet on (sorry, "trade based on your view of") future events. Like elections. Or sports games. Or whether the Fed raises rates.

The CFTC approved Kalshi in November 2020 to operate as a "designated contract market." Fully regulated. Legitimate. Not gambling.

There was just one problem. When Kalshi tried to offer contracts on the 2024 presidential election, the CFTC said no. Election contracts might be considered gambling, the commission worried. Also maybe market manipulation. Also maybe undermining democracy by turning elections into betting opportunities.

This is where the story gets good. Most companies facing regulatory rejection would negotiate, compromise, maybe try again next year. Lopes Lara proposed something different: sue the CFTC.

In late 2023, Kalshi filed a lawsuit against the Commodity Futures Trading Commission. The company argued that the commission had no legal authority to block election contracts. After all, Kalshi was already a regulated exchange. The CFTC had approved its operations. Election contracts were just another type of event contract.

Kalshi won. A federal judge ruled in September 2024 that the CFTC had overstepped its authority. Election contracts were legal. The floodgates opened.

During the 2024 election, Kalshi processed $1.97 billion in election contracts. The company captured 62% of the global market share for election betting. Weekly trading volumes exploded. The valuation quintupled in six months.

And here's the kicker: 80% of current trading volume is sports betting. The thing that DraftKings and FanDuel spent decades fighting to legalize, navigating state-by-state regulations, paying licensing fees, submitting to oversight. Kalshi just calls it "event contracts," operates under CFTC approval, and prints money.

Who Pays

The genius of this con is that nobody thinks they're getting screwed. People placing bets think they're making sophisticated trades on a regulated exchange. States that banned sports gambling think the CFTC is handling oversight. The CFTC thinks it's regulating financial derivatives, not sports betting. Investors think they're funding financial technology innovation, not a gambling platform.

But here's who actually pays. DraftKings and FanDuel, which spent years and billions building legal sports betting infrastructure, now face competition from platforms that bypassed the whole regulatory gauntlet by using different words. Traditional futures exchanges, which operate under heavy CFTC oversight and capital requirements, now compete with prediction market platforms that face lighter scrutiny. And states that carefully regulate gambling to protect consumers and capture tax revenue watch betting volume flow to CFTC-regulated platforms that don't pay state gambling taxes.

The regulatory arbitrage is perfect. Sports betting is heavily regulated at the state level. Financial derivatives are regulated at the federal level by the CFTC. Call sports betting "event contracts," get CFTC approval, and suddenly you're operating in a different regulatory universe with different rules, different oversight, and different economics.

The numbers tell the story. Kalshi's weekly trading volume exceeds $1 billion. The company went from 2 million users to 5 million in 2025. Revenue projections hit $500 million annually. All from a platform that's 80% sports betting but isn't subject to state gambling regulations because it's technically a CFTC-regulated derivatives exchange.

The Real Scandal

The part that should make you angry isn't that Lopes Lara and Mansour got rich. Good for them. They spotted a regulatory gap and drove a truck through it. That's entrepreneurship.

The scandal is that this regulatory arbitrage was available at all. That you can take an activity that's heavily regulated in one framework, rename it, get approval under a different framework, and suddenly the rules change. That federal regulators approved a business model that's 80% sports betting but isn't subject to gambling regulations because the magic words "event contracts" and "prediction markets" apparently transform betting into finance.

Think about what this means. For decades, sports gambling was mostly illegal because legislators decided gambling was harmful, exploitative, or morally wrong. Then in 2018, the Supreme Court said states could legalize it if they wanted. Most states created careful regulatory frameworks: licensing requirements, consumer protections, problem gambling resources, tax collection.

Then Kalshi comes along and says "we're not gambling, we're financial derivatives" and the CFTC says "okay" and suddenly you can bet on sports through a federally regulated exchange that doesn't have to comply with any of those state frameworks.

The telling detail is the investor list. Sequoia Capital. Andreessen Horowitz. Paradigm. Y Combinator. These aren't gambling industry investors. These are Silicon Valley and crypto venture funds that fund "financial technology." Because Kalshi isn't gambling. It's fintech. It's innovation. It's "democratizing access to prediction markets."

And it's worth $11 billion because it figured out that calling gambling something else makes it legal.

The competitor dynamic makes it even clearer. Polymarket, Kalshi's main rival, operated in regulatory gray area for years. Then in October 2025, the New York Stock Exchange's parent company invested $2 billion in Polymarket at an $8 billion valuation. That investment made Polymarket's 27-year-old founder, Shayne Coplan, the youngest self-made billionaire (male division).

So now you have the New York Stock Exchange investing in prediction markets. You have major venture capital firms pouring billions into platforms that are 80% sports betting. You have federal regulators treating these platforms as financial exchanges rather than gambling operations. And you have founders in their twenties becoming billionaires by figuring out that regulatory arbitrage beats regulatory compliance.

The Pipeline That Built This

Here's another detail worth noting. Lopes Lara spent her college summers interning at Bridgewater Associates (Ray Dalio's hedge fund) and Citadel (Ken Griffin's hedge fund). These aren't normal college internships. These are the most competitive finance internships in the world. You don't get them without connections, credentials, and the kind of polish that makes Wall Street comfortable.

Then she and Mansour both interned at Five Rings Capital in New York. That's where they came up with the Kalshi idea. They were working in finance, surrounded by people who trade derivatives, and they realized: everything people bet on in gambling is just an event with a binary outcome. Why can't you trade those outcomes like any other derivative?

This is how Wall Street thinks. Everything is a tradable asset. Elections, sports games, Oscar winners, whatever. If people have opinions about future outcomes, create a market. If regulations don't allow the market, sue the regulators.

And it works. Because the people running venture capital firms went to the same schools as the people running federal regulatory agencies. They speak the same language. They understand that calling something "event contracts" instead of "bets" isn't just semantics—it's the difference between heavy state gambling regulation and lighter federal derivatives oversight.

The ballet backstory makes good copy. Lopes Lara trained at Brazil's Bolshoi Theater School. Teachers held lit cigarettes under her thigh to test how long she could hold it up without getting burned. She endured 13-hour training days. She performed professionally in Austria before giving up dance to study computer science at MIT.

That's a great founder story. Grit, discipline, immigrant determination. The kind of narrative that makes for good Forbes profiles and investor pitch decks.

But the relevant part of her story isn't the ballet. It's the Bridgewater and Citadel internships. It's the MIT computer science degree. It's understanding how derivatives regulation works and recognizing that calling gambling "prediction markets" changes which regulators have jurisdiction.

The Bottom Line

Sports betting is now a financial instrument. You can trade on Monday Night Football like you trade corn futures. The regulatory framework that took decades to build around gambling doesn't apply because this isn't gambling—it's finance.

And two 29-year-olds who figured this out are now worth $1.3 billion each.

The system isn't broken. It's working exactly as designed. Regulations exist to control activities that lawmakers decided need controlling. But regulations only work if you can't bypass them by calling something a different name. When you can take sports betting, call it "event contracts," sue federal regulators to force approval, and walk away with an $11 billion valuation, the regulations aren't controlling anything. They're just obstacles for people who don't know the magic words.

DraftKings and FanDuel fought for years to legalize sports betting. They paid lawyers, lobbied legislators, built compliance infrastructure, submitted to state oversight. They won, eventually. Sports betting is legal in most states now, heavily regulated and heavily taxed.

Then Kalshi showed up and said "we're doing the same thing but we're calling it derivatives" and the CFTC said "okay" and now Kalshi processes $1 billion in weekly trading volume without dealing with any of that state-level oversight.

This is how you build a billion-dollar company in America: find a regulatory gap, drive through it, and sue anyone who tries to stop you. Investors will fund you. The business press will celebrate you. And when you're worth $1.3 billion at 29, everyone will write stories about your inspirational journey from ballerina to billionaire.

Just don't call it what it is: sports gambling with better branding.

💰 Your Move

What do you think? Is this financial innovation or regulatory arbitrage with a better marketing budget? Drop your take in the comments.

Share this if you're tired of watching Wall Street rebrand things and pretend they're not exactly what they obviously are.

Subscribe for more stories about how the con actually works, who profits, and who pays the bill.