Kim Zito’s Facebook page looks like any other North Jersey success story. Two tiny dogs on velvet cushions. Glittering countertops. Her blond hair never out of place. A caption about gratitude, right under a Louis Vuitton purse. The comments are predictable: “So proud of you babe.” “You’re glowing.” No one ever asks where the money comes from.

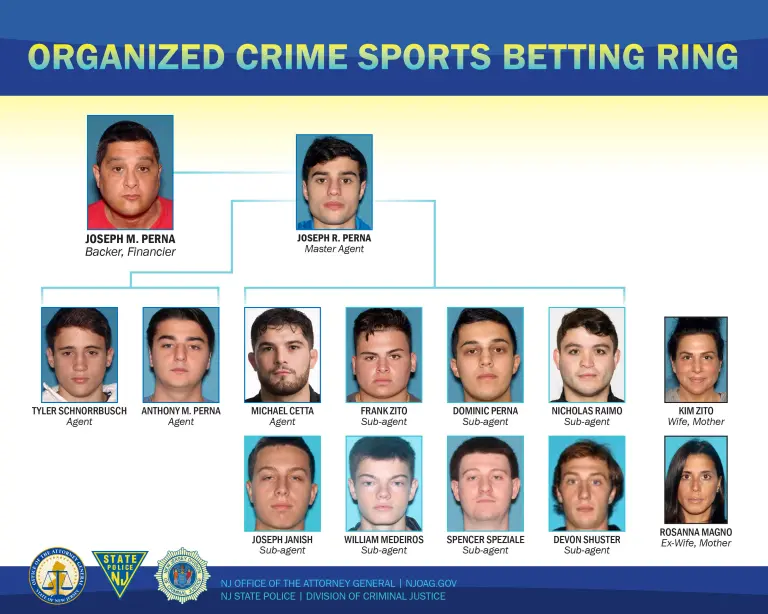

Behind those curated squares, prosecutors say, was a suburban side hustle worthy of a Martin Scorsese sequel. Zito, 53, and her friendly rival, Rosanna Magno, 52, were allegedly taking cash skims from an online sports betting ring linked to the Lucchese crime family. Police say the ring took in more than two million dollars, mostly from young men who thought they were betting anonymously through some offshore website. Behind the screens, there was family—always family.

Zito is married to Joseph “Little Joe” Perna, reputed Lucchese soldier. Magno is his ex-wife. Both raised their sons in football jerseys and private-school sweatshirts. The boys, now in their early twenties, supposedly ran the day-to-day gambling network: taking bets, paying out, keeping the digital books. The mothers kept the money clean, the feds say. The fathers kept the old connections alive.

In photos, Zito floats through life like an understudy from Real Housewives of New Jersey. Champagne, tan lines, motivational quotes, photos with her son Frank celebrating touchdowns. Her following includes ex–cast members from Bravo, President Trump, and a few earnest Second Amendment pages. The algorithm loves her. For most people, she’s just another North Jersey woman who made it out of Essex County with good hair and a mortgage.

Magno took a different approach. Her LinkedIn is tight and corporate, the language pure HR: “regulatory adherence,” “enhancing engagement,” “aligning client needs with fiduciary best practices.” Clean font, polite smile, minimal makeup. The only social presence left after the charges dropped. Her neighbors describe her as quiet but generous, “the one who brought cannoli to the block party.” Always the quiet ones.

According to investigators, the Luccheses have modernized. Bookmaking is no longer conducted in basements or cigar shops. The mob uses cloud-hosted servers now. Telegram chats instead of payphones. Wire transfers that trail through Venmo before vanishing behind encrypted ledgers. And it’s not the old enforcers doing the work—it’s their sons. Athletes, college kids, social media naturals. The foot soldiers of the algorithmic mob.

The women’s homes look as expensive as they’re supposed to: Fairfield for Zito, Oakland for Magno. One valued at eight hundred thousand, the other slightly less. Big enough to look legitimate, not flashy enough to draw suspicion. White fences, quiet driveways, the smell of cut grass and Dior perfume. The kind of houses designed to reassure people that everything out here is normal.

It didn’t last. In November 2023, federal investigators say Zito accepted envelopes of gambling proceeds just before Christmas. The following spring, Magno was pulled over and allegedly tried to hide notebooks—later identified as betting ledgers—while officers searched her SUV. That was the unraveling point. The notebooks matched the usernames and digital ledgers tied to the Lucchese ring.

The other names in the indictment read like a reunion list from New Jersey sports programs. Ex–Rutgers wrestler Michael Cetta, 23, a nephew of Magno. Dominic Perna, 23, cousin to the others. All involved, the state says, in distributing illegal gambling funds between 2022 and 2024. A network that stretched down the East Coast and across a digital one.

If this all feels familiar, it is. The Luccheses have been recycling the same template for decades. The front changes—construction unions, waste hauling, then internet gambling—but the rhythm is the same. The illusion of family and the gravity of loyalty, things that sound pure but break everyone who believes in them.

Scrolling Zito’s Instagram now feels like performance art. The slogans about loyalty. The filtered selfies. The post about “never apologizing for living your truth.” Every photo timestamp becomes a breadcrumb. The agents didn’t need wiretaps. They had her feed. As one investigator put it, “People tell on themselves better than any bug ever could.”

Both women have pleaded not guilty. Their attorneys are pointing at “bad information” and “tainted digital evidence.” But around Bergen County, it’s not about innocence anymore. It’s about performance. In the space between a prayer post and a police mugshot, the truth stops mattering. What matters is the story.

Stories are what the Luccheses have thrived on for a century. They build them, fund them, and live inside them until the walls come down. The myth of family becomes a mortgage. Loyalty becomes debt. Whether that debt is paid with blood or Bitcoin almost doesn’t matter.

And if there’s anything New Jersey has perfected since Tony Soprano, it’s pretending that corruption looks glamorous. Fake lashes. Fresh veneers. A filter and a caption about gratitude. The ring light doesn’t care where the money came from.